From an interview with Bridget Penney conducted by Maxi Kim, January 2011.

MK: In 1993 you started Invisible Books with Paul Holman and over the next six years Invisible Books published ten books: six collections of poetry, two anthologies and two books you have loosely described as belonging in the realm of cultural studies. What was that experience like? Many of my friends are either thinking about starting a small publishing outfit or are in the process of starting one. What kind of advice would you give emerging publishers? What is the most common mistake that young publishers should avoid?

BP: When Paul and I started Invisible Books the internet didn’t really exist in any form that would be recognisable to most people using it today so publishing online wasn’t an option. In fact writing about what we did then seems like ancient history because the production of books has changed so radically. The idea of print-on-demand; making up physical copies of a book only when you had customers for them, was unimaginable. The minimum print run for us to put out perfectbound books at what we considered a reasonable price was five hundred copies. We used a printer called The Book Factory for several titles and they were great, they didn’t care what size or shape the books were as long as they were A4 or under so we did one book, Idir Eatortha, as A4 which suited the ‘open field’, page as important unit of composition, nature of Catherine Walsh’s work. We did Off Ardglas as square, because Rob MacKenzie’s poems had long lines which we could avoid breaking that way and there were some in double columns which couldn’t have been presented well on a more conventional page.

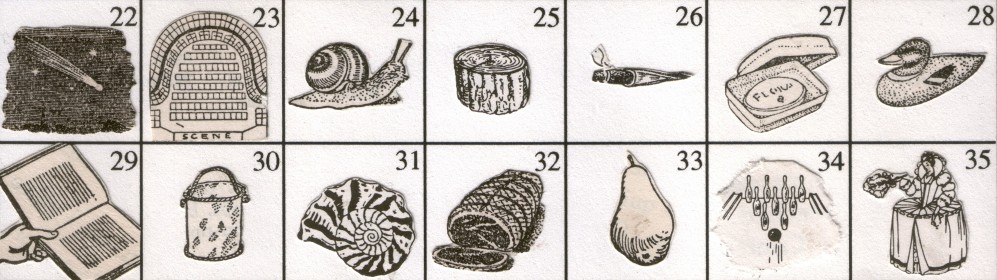

Given the experimental work we were publishing I think I at least was naive in expecting the books to break even within a reasonable time frame. We were lucky because we managed to get some funding for four of our projects; we got £500 which paid for the printing of our second book, The Invisible Reader, from the Poplar Arts Trust which we’d seen a tiny ad for in the free local paper – I always assumed no one else had applied. We never had any idea of developing as a business so we didn’t factor in paying ourselves, advertising or anything grown-up, we just wanted money to pay for the printing of the books and what were really very token payments for the writers and artists were were working with. We benefited hugely from people’s generosity with their time and creative input and I think the experience of working with the people we published was what was most fun about the whole project. A most honourable mention is due to Woodrow Phoenix, author of the very fine graphic novel Rumble Strip, who designed our logo, several covers and three whole books including Loose Watch; a Lost and Found Times anthology where he managed to pull the most heterogeneous collection of graphics and texts from a twenty-two year span of Lost and Found Times magazine together in a way that paid tribute to the look of the originals and became an elegant piece of design. Loose Watch remains the book I’m most pleased we did. Almost all our other titles were pretty much fully-formed when they came to us and, if we hadn’t existed, I’m sure another small press would have published them sooner or later. John M. Bennett (co-founder and editor of Lost and Found Times magazine) was very gracious when we first approached him with the idea of publishing the anthology and remained so throughout the frenetic process of selecting and arranging material. We ended up with one hundred and seventy contributors, mostly outside the UK, and had to post them all contributors’ copies (we had somehow neglected to budget for postage) but this was the occasion on which I felt the press came closest to achieving what we set out to do.

I think we ignored most of the well-meaning advice we were given – choosing a name which people would and did find irresistible to joke about; producing books which were and looked cheaply produced rather than expensive limited editions and came in non-standard sizes and shapes – so I really don’t feel qualified to offer any. And methods of production and distribution have changed so much that a lot of our experience just isn’t relevant. But the reason we started Invisible Books was because we wanted to do something that we couldn’t see happening anywhere else at the time. We wanted to make work we thought interesting more widely accessible and also aspired to produce books that would fit to the work, not the other way round. I certainly wouldn’t claim we were completely successful in either of these aims and maybe they weren’t that compatible with each other but you never know until you try.

Bill Griffiths interview

Compendium, Camden Town, 1995

On Rea Nikonova

Spike Island, Bristol, 2011