Rea Nikonova: Twenty Visual Poems. Afterword by Bridget Penney, October 2011.

Invisible Books first encountered Rea Nikonova’s work through Lost and Found Times magazine in the 1990s. Examples of her work were included in Loose Watch: ‘A Lost and Found Times’ anthology which we co-edited with John M. Bennett in 1998 and we are delighted to be publishing her again. As the visual poems included here don’t reflect the full range of her practice, it seemed a good idea to provide a little more information about her cultural activities and background.

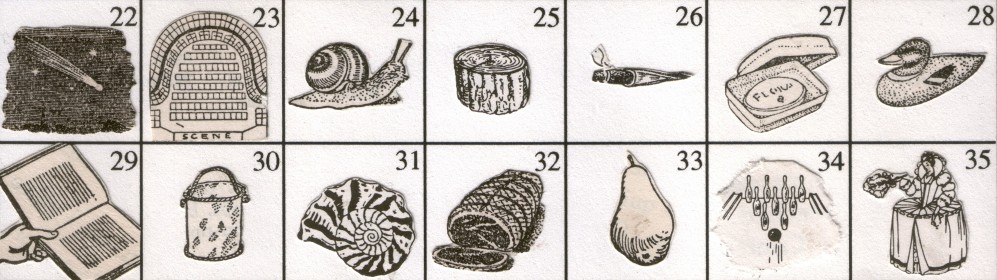

Rea (or Ry) Nikonova was born Anna Tarshis in 1942 in Yeysk, Russia, and has been involved in literature since 1959 and painting since 1962. She was a founder member of the ‘Uktuss School’ (1965-1974), a group of artists and poets in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg); and editor (with Serge Segay, whom she married in 1966) of the underground journal Nomer (Number). Nomer usually appeared every three months – for thirty-five issues in all – in a unique, handwritten copy: If more than five copies had been made it would have been considered an illegal publication and confiscated by the Soviet authorities. Some issues were seized by the KGB when the group was suppressed in 1974 but others are held in the archive of samizdat literature in Forschungstelle Osteuroca (Research Centre for East European Studies) at Bremen University. Later that year Nikonova and Segay moved to Yeysk where they lived until emigrating to Germany in 1998.

From 1979-1987 Nikonova and Segay edited Transponans (Transposition); the main organ of the Transfuturist Poets group (1980-1986) to which they both belonged. Inna Tigountsova writes ‘Their transposing involved analyzing different types of art from unorthodox perspectives, for instance exploring the qualities reminiscent of the literary text in painting and vice versa.’ Transponans came out, initially four, then six times a year, in an edition of five handmade copies. Thirty-six issues appeared, of which several had unusual geometrical shapes. The Bremen archive holds a complete set.

Nikonova’s theoretical writings from this period contain suggestions for books in the form of a disc, a pyramid, a pinwheel, a mill, pillow, pillowcase, briefcase, cylinder, mosaic, bracelet, etc. All potentially disrupt and redefine the experience of reading in different ways; encouraging the reader to actively (re)create the text. For example, the book-pillow, made by the editors of Transponans for the jubilee of the Futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikov (1885-1922) (who during his travels round Russia kept his manuscripts in a pillowcase), enables sheets to be shuffled in any order and turns the act of reading into a performance. The image of the pin-wheel or mill, introducing a mechanical kinetic element which further randomizes the experience of reading, bringing Liliane Lijn’s poem machines to mind. Both draw from ideas associated with Dada and movements which developed from it yet to some extent existed in parallel. Until the mid 1980s, Nikonova’s opportunities for interaction with Western artists were somewhat limited.

Building texts which can be read in several different directions is another way to reject the idea of a fixed authorial presence. Nikonova’s vector poems and architectural treatments (examples of both included in Twenty Visual Poems) demonstrate multiple ways in which the reader can choose to guide him or herself through a text. Gestural poems and sound pieces show yet another approach but the absence of words does not represent a refusal of language, rather an attempt to extend its usefulness. The term Zaum (can be translated as ‘trans rational’ or ‘beyond sense’) was coined by Aleksei Kruchenykh in 1913 and has been employed by the Futurists and Transfuturists. According to Gerald Janecek, it can be defined as experimental poetic language characterized by indeterminacy in meaning. Another direction which has been explored by Nikonova in the spirit of Zaum is that of translinguistic collaboration. Again, these collaborations concentrate on processes and forms, rather than social myths, to create what John M. Bennett describes as ‘totemic linguistic artifacts’.

Since 1986 Nikonova’s work has been shown in more than thirty group exhibitions of visual poetry in Mexico, Italy, Germany, Brazil and Australia; and she has had solo shows in Germany, Italy and Japan. In 1994 she participated in International Sound Poetry Fests in Berlin and Budapest. In recent years she has contributed to numerous Russian and Western journals/projects, including Field Study and Lost and Found Times. Her first book publication in Russia, in connection with her performance at the Sidur Museum in Moscow, took place in 1997. Her work has also been published in book form in the UK (by Writers Forum), Germany, USA and Canada.

Bill Griffiths interview

Compendium, Camden Town, 1995

Maxi Kim interview

Spike Island, Bristol, 2011